25 March 2019

|

In his latest expert stamp guide, Dr David Parker looks at what Belgium stamps of 1914 to 1919 can tell us about the country's buildings, monuments and wartime publicity.

The small state of Belgium suffered badly at the hands of Germany in 1914, and throughout its occupation – and the effects of the loss of life, destruction of towns, and dislocation of industry lasted long after 1918. In early August 1914 German armies swept through southern and central Belgium on their advance into north-eastern France and towards their primary target of Paris and a knockout blow to France.

With France out of the war Germany could turn to face the Russian armies mobilizing in the east – but far more slowly - and avoid a war on two fronts. With speed of the essence, any Belgian resistance was dwelt with savagely and the Germans thought nothing of bombarding towns they thought capable of impeding their advance or harbouring resistance fighters.

Not all the hundreds of stories of widespread German atrocities towards civilians ands captured troops were true, but modern historians such as Alan Kramer are convinced that, wartime propaganda aside, many accusations were valid. (1914-1918 online: Alan Kramer (2017) Atrocities in International Encyclopedia of the First World War)

The Germans occupied most, but not quite all, of Belgium. The Belgian government exiled itself to a suburb of Le Havre in France from where it continued to issue stamps. However most Belgians were obliged to use German stamps overprinted ‘Belgian’ and values in centimes and francs. The only exception was a small enclave east of the River Yser and Ypres in the far north-west bordered by France to the west and the sea to the north where until the Armistice in 1918 King Albert of the Belgians and a surviving portion of his army faced the Germans across the northernmost sector of the Western Front.

Patriotism on stamps

Not surprisingly Belgian stamps from this period were highly patriotic and used historic associations to rally the nation and maintain unity. One perennial problem was the enmity that had existed since Belgium gained independence from the Netherlands in 1830 between the Dutch speaking Flemings of the north and French speaking Walloons of the south. In 1893 Belgian stamps recognised the divide by using both languages.

During the occupation the Germans sought, with a little success, to exploit this division by overtly favouring the Flemings over the Walloons. The only Belgian stamps issued before the country was occupied appeared in support of the Red Cross Fund on 2 October 1914. Three featured the unifying portrait of the embattled king, and three the unifying image of two Belgian soldiers – one wounded, the other holding a flag aloft – by the celebrated Merode Monument in Martyrs Square, Brussels.

During the occupation the Germans sought, with a little success, to exploit this division by overtly favouring the Flemings over the Walloons. The only Belgian stamps issued before the country was occupied appeared in support of the Red Cross Fund on 2 October 1914. Three featured the unifying portrait of the embattled king, and three the unifying image of two Belgian soldiers – one wounded, the other holding a flag aloft – by the celebrated Merode Monument in Martyrs Square, Brussels.

The Merode Monument

Erected in 1893 in Art Nouveau style, the Merode Monument honoured the memory of Count Frederic de Merode who became a national hero when he was killed in battle during the 1830 war of liberation. His aristocratic family owned vast estates and had served previous rulers of the Low Countries as soldiers and diplomats for many centuries, but seized the opportunity to further the cause of independence after the final defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte. One of the monument’s inscriptions, Mort pour l’independence de la patrie (Dying for the nation’s independence), was particularly poignant in 1914.

The former glory of several historic Belgian cities devastated by the Germans provided adorned three stamps in a set issued by the government in exile in October 1915. The 35c featured the thirteenth century Cloth Hall at Ypres with its long row of early pointed arches and soaring bell tower that was destroyed by German artillery fire in the battles raging around the strategically sited town. The 40c showed Dinant, much of which had been destroyed as the French and Germans fought over it in August 1914. In their anger and frustration the Germans summarily executed 674 civilians. The 50c portrayed the famous library in Louvain which rampaging German soldiers deliberately set on fire, along with its priceless documents, in August 1914. They also massacred 300 civilians.

35c Cloth Hall, Ypres, 40c Dinant, 50c Library at Louvain (from set 1 October 1915+)

Alongside stamps featuring the three kings of the Belgians, and King Albert inspecting troops at Furnes (Veurne) in the Yser salient, the set had two highlighting particular crises in Belgium’s short history. The 1f commemorated the freeing of the Western Scheldt from Netherlands’ authority. There was little friendship between the neighbours, and after Belgium wrestled free in 1830 the Netherlands continued to block Antwerp’s access to the sea along the waterway.

Its excuse was that ever since 1648 when it had secured independence from Spanish Hapsburg control it had been granted control of the river’s southern bank. However in recognition that the economy of the new state of Belgium’s depended on overseas trade, international pressure forced the reluctant Netherlands to back down in 1832. The Dutch, however, continued to demand tolls from Belgian ships until 1863.

1f Freeing of the Scheldt and 2f Annexing the Congo (from set 1 October 1915)

The 2f stamp featured what appears to be an Arab (no doubt a slave trader) kneeling before a Belgian district commissioner standing by a flag standard supported by Congolese natives. It seems to portray a benevolent Belgian administration with the Congolese welcoming Belgium’s occupation and hostility towards the Arab slave traders. The picture is more than a little disingenuous, even though Arab slave traders had penetrated parts of the Congo.

The truth was that between 1885 and 1908 King Albert’s father, King Leopold II, had ruthlessly exploited the Congo as a de facto private fiefdom until the appalling scandals of forced labour, cruel treatment, and high death rate among the Congolese finally obliged the Belgian government to annex the vast region. Things got a little better, and certainly King Albert (reigned 1909-34) attempted to improve conditions.

During the war Anglo-Belgian forces, supported by thousands of Congolese bearers, fought German forces in German East Africa, and by 1918 they had ‘freed’ much of Germany’s colonial territory. Indeed Germany’s own record of African colonialism was severely marred by its harsh treatment of local tribes.

The medieval perron at Liege (19 July 1919)

In July 1919 the first Belgian stamp released after the war featured the famous ‘perron’ at Liege. A perron was a stone column surmounted by an orb bearing a cross that, in medieval times, became places where local decisions and laws were announced and justice dispensed. They came to represent the liberties of the city. Liege’s perron, which incorporated a highly valued fresh water fountain, was forcibly removed in 1468 by Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, as part of his punishment for the Prince-Bishop of Liege’s involvement in a third revolt during that decade.

Many inhabitants were slaughtered, the city’s walls were dismantled and its civic liberties severely reduced – as the absence of the perron emphasized. In 1477 Charles was defeated and killed in battle at Nancy, leaving only a daughter, Mary, who later married the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian I. Burgundy became a Hapsburg possession although the cause of endless dispute with France.

As far as Liege was concerned in 1478 the perron, and the civic liberties it represented, were restored amidst great celebration. And after Belgium’s liberty was restored in 1918, the inscription carved into the perron in 1478 that ended These times of bitter servitude have passed, and here am I on your breast, O my mother once again had particular significance.

QUICK LINK: Albania and the inexorable rise of Zog

Dr David Parker is the author of European Stamp Issues and the First World War, published by Halsgrove Publishing.

Dr David Parker is the author of European Stamp Issues and the First World War, published by Halsgrove Publishing.

The book provides a fascinating portrait of the turbulent decades of the early twentieth century, revealed through miniature works of art that are in themselves important historical sources.

ISBN 978 0 85704 330 6, hardback, 297x210mm, 168 pages. Published October 2018.

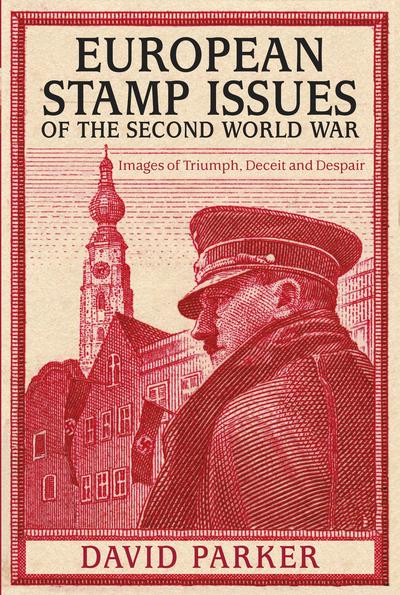

Dr David Parker's book European Stamp Issues of the Second World War: Images of Triumph, Deceit and Despair is published by History Press. This remarkable collection examines and interprets the stamps of twenty-two countries across western and eastern Europe.

Dr David Parker's book European Stamp Issues of the Second World War: Images of Triumph, Deceit and Despair is published by History Press. This remarkable collection examines and interprets the stamps of twenty-two countries across western and eastern Europe.

The glorification of the Führer and Germany on the stamps of countries he most oppressed was inevitable, but many issues are ambiguous and indicative of the rival ethnic and political forces striving to attain influence and power. Desperate to unite the people, Soviet Russia resorted to images of the nation’s heroic achievements under the Tsars; the mutually hostile puppet states Hitler and Mussolini allowed to emerge out of conquered Yugoslavia lost no time in issuing stamps proclaiming their cultural diversity; and Vichy France sought to justify its existence with issues linking past glories under Louis XIV and Napoleon with an equally glorious future alongside Hitler.

These and many more stories reveal the aspirations, assumptions and anxieties of so many nations as their destinies hung in the balance.

ISBN 978-0750959155. Published May 2015.